The Backstrap Loom

of

Jacaltenango, Guatemala

|

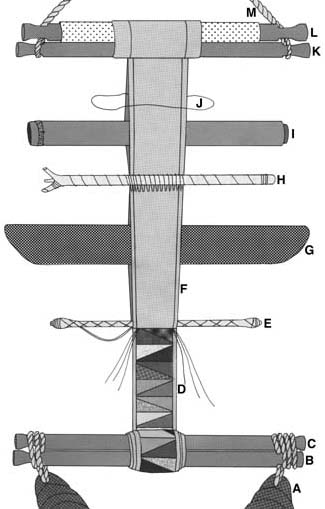

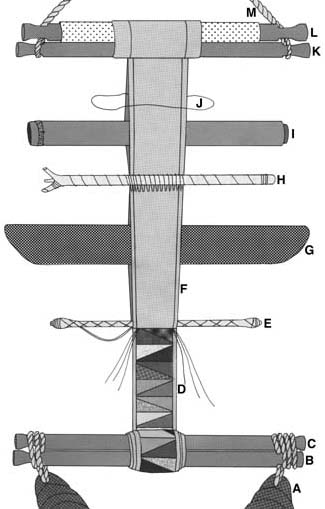

The "Y" shaped tie cord (M) has a two

inch loop on each of its two short ends. The long end of the cord averages fifty three

inches in length, while each of the shorter ends average fourteen inches.

The lease

cord (J); is tied into the shed while the warp is still on the warping frame

where the shed bar will be positioned. The lease cord maintains the order of the warp

threads and remains until the hair sash has been completely woven. When the shed roll

slips out of position (this sometimes happens when the loom is not under tension), the

lease thread is lifted to form an opening, then the shed roll is slipped into place. The shed

roll (I) divides the warp in half. In Jacaltenango it is always constructed of a

hollow cane or bamboo. It often has pebbles or seeds inside the core to make noise as the

woven hair sash is beaten. The cane's natural joint forms one end of the container

and the other end is plugged with paper after the seeds or pebbles have been inserted. The

shed roll averages three quarters of an inch in diameter and is the same length as the end

rods and like them, turns brown and shiny with age and use. The heddle rod (H) consists

of a debarked stick, approximately eight inches long, that has three or more prongs on one

end. The heddle thread is spirally wrapped around the stick. The heddles are actually

closer together than they appear in the illustration. The heddle rod is also highly

regarded by the weaver; she will not part with it. When commissioning pieces still on the

loom, I had to provide a set of four end rods, a beater, and a heddle stick because of the

attachment that weavers have for these loom parts. The beater (G) is made

of a heavy wood and is usually around eleven inches long by one and a quarter inches wide.

The thick rounded top edge tapers to a sharp knife-like edge on the bottom. The beater is

perhaps the most precious part of the loom to a weaver. They are sometimes handed down

from mother to daughter. The warp (F) may be either single or double for

the hair sashes. The floral and the striped geometric hair sashes are usually woven with a

single warp. The other geometric hair sashes are woven with a paired warp. The weft

bobbin (E) is approximately seven inches long. The weft is spirally wrapped

around the stick back and forth. The supplementary wefts (D) are extra.

If they were to be removed, the integrity of the woven cloth would remain intact. The cloth

end rods (B and C) and the warp end rods (K and L) need only be

long enough to sustain the warp and to comfortably allow the loom to be stretched between

a support and the weaver (usually the width of the warp plus approximately four inches on

each side). All four of the rods average ten inches in length and a half inch in width.

The end rods of the loom are precious to each weaver. They are esteemed and coveted when

they are old and brown. An average size for backstrap (A) is two inches

by eighteen inches with two fifteen inch loops. |

|

For a closer look, you might enjoy Maya Hair Sashes Backstrap Woven in Jacaltenango /

Cintas mayas tejidas con el telar de cintura en Jacaltenango, Guatemala,

a bilingual book that features this Jakaltek backstrap loom, backstrap weaving, and the beautiful hair sashes of the Jakaltek women, from both anthropological and artistic perspectives. The 176 page paperback book includes 38 illustrations, 116 black and white photographs, and 15 color photographs. (ISBN 0-9721253-1-0). You may order a signed copy with a credit card by clicking the "buy now" button on the left (only for shipping to an address in the United States). This price includes free shipping in the United States . If you would like a personalized dedication with the signature, please mention it in the "instructions to merchant" box on the PayPal page. |

Maya Hair Sashes . . .

Book Reviews:

Journal of Latin American Anthropology, November 2005

. . . The precise documentation of the tools and

techniques of the weaving process of the hair sash in Carol Ventura's bilingual

work is a propos here since it deals with the preservation of knowledge of the

tradition. For Ventura, the artist and art historian, 1986 was the culmination

of four and one-half years of working with the Jakaltek weavers in Guatemala.

Her view of the learning process at that time, which included learning by

observation and use of the toy loom, accords with Greenfield. Ventura returned

in 1996 and in 2002. Although in 1986 weaving was an important activity that

established group identity and social cohesiveness, by 2002 weaving was rapidly

disappearing. The weaving cooperative had become a general store and there was

less foreign demand for hair sashes and wall hangings. The hair sash designs had

evolved from simple geometric patterns to elaborate designs appropriated from

German silk ribbons. It was the only item of local dress still woven in 2002 in

Jacaltenango. This and the fact that Jakaltek textiles are still a commodity

will, in Ventura's opinion, keep weaving alive in the near future. The picture

given by Ventura of the changes between 1986 and 2002 is very much in keeping

with those mentioned in the previous two books. Communication and contact via a

road system and technology; the telephone, television, and the Internet -

provide contact with the broader world. More schools and a university branch

have widened horizons. A cash economy and the remittances sent by emigrants have

enabled economic life will beyond subsistence levels, much as the

commoditization of textiles has empowered women. . . Virginia Davis

Choice,

November 2004, 42.3: 473

Contemporary Mayan material culture has received cursory attention from scholars

outside of its relevance to ancient Mesoamerica studies. Textile production and

trade have been intrinsic to the life of Mayan peoples since before the Common

Era, but much about their history remains unknowable. Ventura (Tennessee

Technological Univ.), a compassionate historian and skilled weaver, documents in

detail the history, method, style, and patterns in the backstrap-woven hair

sashes worn and sold by Jakaltek women living in a remote area of modern

Guatemala. Sections on Mesoamerican religion and mythology and pre-Columbian

symbolism of weaving, in conjunction with a useful bibliography in English and

Spanish, makes this a key resource for historians, anthropologists, and

practitioners. Ventura contributes the first comprehensive account of the

backstrap looming method and the conservation and transformation of traditional

patterns and their meanings, including templates and step-by-step instructions

for weavers. All documented areas are supported by carefully composed

photographs of Jakaltek people and places, especially women working at their

looms, and legible close-ups of many specific sashes. Unfortunately, very few

illustrations are in color; color is significant to several designs that, in

some cases, have revealed for generations the social status of individual

Jakaltek women. Summing Up: Highly recommended. General readers; lower-division

undergraduates through professionals. M. R. Vendryes, York College, CUNY

Handwoven, May/June 2004: 20-21

Carol Ventura, also the author of books on

tapestry crochet under the name Carol Norton, learned to weave Jakaltek hair

sashes while serving as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Guatemala in the late 1970's.

She learned to speak Spanish and the local language, Popti', and spent several

years working with the Jakaltek weavers of Jacaltenango. Her doctoral

dissertation on hair sashes was published in 1989. The first edition of this

book was published in 1996 by Yax Te' Press.

The Jakalteks have lived in the highlands

of northwest Guatemala since pre-Columbian times. The women maintain their

traditional clothing style. The hair sash is the only item that is still locally

woven. It is an important trade item and is exported worldwide.

While the designs on the sashes may appear

to be embroidered, they are actually created as the fabric is woven. Jakalteks

use a double-faced supplementary-weft brocade technique to create a variety of

geometric and pictorial motifs on a warp-faced fabric.

This is more than a book documenting hair

sashes. The technical information includes a valuable analysis and comparison of

forty-five hair sashes collected between 1927 and 1989. In addition, a wealth of

historical background is presented in a very readable style. One chapter

summarizes the development of weaving in the area, beginning with the first

evidence of pre-Columbian textiles. The fibers and the tools used to create the

hair sash, as well as the double-sided brocading technique used by the weavers,

are all well documented. Black-and-white photos show the steps involved in using

the warping frame and the loom - there is even a photo showing a blind man

making a ply-split backstrap from 2-ply sisal. Another chapter documents the

physical and spiritual importance of weaving and clothing to the Jakalteks that

includes sections on pre-Columbian cosmology, weaving deities, and the symbolism

of huipiles, hair sashes, colors, and motifs.

Many interesting footnotes supplement the

text, along with charming photographs of women warping and weaving. The four

pages of color photographs show over fifty sashes, and the instructions will

enable readers to reproduce the designs. Anyone interested in weaving should

enjoy this book, especially those who want to know more about Guatemalan

Textiles. Linda Hendrickson

página en español

Links:

Backstrap Weaving in Jacaltenango, Guatemala

Backstrap Weaving School in Santa Maria del Rio, Mexico

Backstrap Woven Shawls of Esperanza Valencia Morra of Morelia, Mexico

Toba Sashes of Argentina with Pickup Motif

Foot-Loom Weaving in Central Mexico

Gobelin Tapestry Weaving in Dolores Hidalgo, Mexico

Songket Weaving in Bali, Indonesia

Tapestry Crochet

Web page, photographs, and text by Carol Ventura. Please look at

Carol's home page to see more about crafts around the world.